How to match GPT-5 at summarization with an RTX 3090 — A quantitative approach

It has been historically complicated to effectively evaluate the quality of summaries, with previous methods either requiring human raters, or using difficult to calibrate automatic grading criteria. Here, I created a new quantitative summarization benchmark, SQUISH (Summarization QUantifiable Information Saving Heuristic). With this precise quantitative metric, I used reinforcement learning to train a 1.7B parameter model matching the performance of GPT-5 reasoning using just an RTX 3090.

Why is summarization important?

There are many practical reasons to use LLMs for summarization. Apple uses summaries in the notification center to aggregate information into a small space. Claude Code uses context compaction to keep as much relevant information inside the context window as possible without running out of space during agentic coding tasks. And ChatGPT users are frequently asking for summaries of large documents and concepts. Ultimately, the goal is to have as much information in as little space as possible.

Previous methods for measuring summaries and training models

Before SQUISH bench, there have been a few different areas of summarization research, each with its own limitations.

One previous method is dataset driven methods, where a large corpus of summaries and documents are used as a labeled dataset to train a summary generating model ([1] [2] [3]). Then these models are evaluated using accuracy metrics like ROUGE, BLEU, and BERTScore. These metrics are essentially checking similarity between generated summaries, and the summaries from the dataset.

The limitation with this methodology is that the accuracy metrics themselves are biased by human generated data. This means that you aren't deriving a target metric unique to summarization, you're just measuring how well your model was able to reflect the dataset.

Later on factuality driven methods arose, attempting to measure the factual consistency between the summary and source document ([3] [4]). These benchmarks take a large step over metrics like ROUGE, BLEU, and BERTScore, as they are directly attempting to measure the quality of a summary using the document itself as a reference, instead of adherence to the pre-defined summaries of the dataset.

However, these methods also have limitations, as they use sensitive heuristics to generate question and answer pairs (e.g. extracting nouns as answers and using a BERT model to generate questions, or splitting the document and summary into sentences for questions and answers). They then generally take a mean of the accuracy of the answers to produce a final score. This makes the final score sensitive to how the pairs are generated, introducing variance.

How else can we model summarization quantitatively?

LLMs are lossy decompression engines

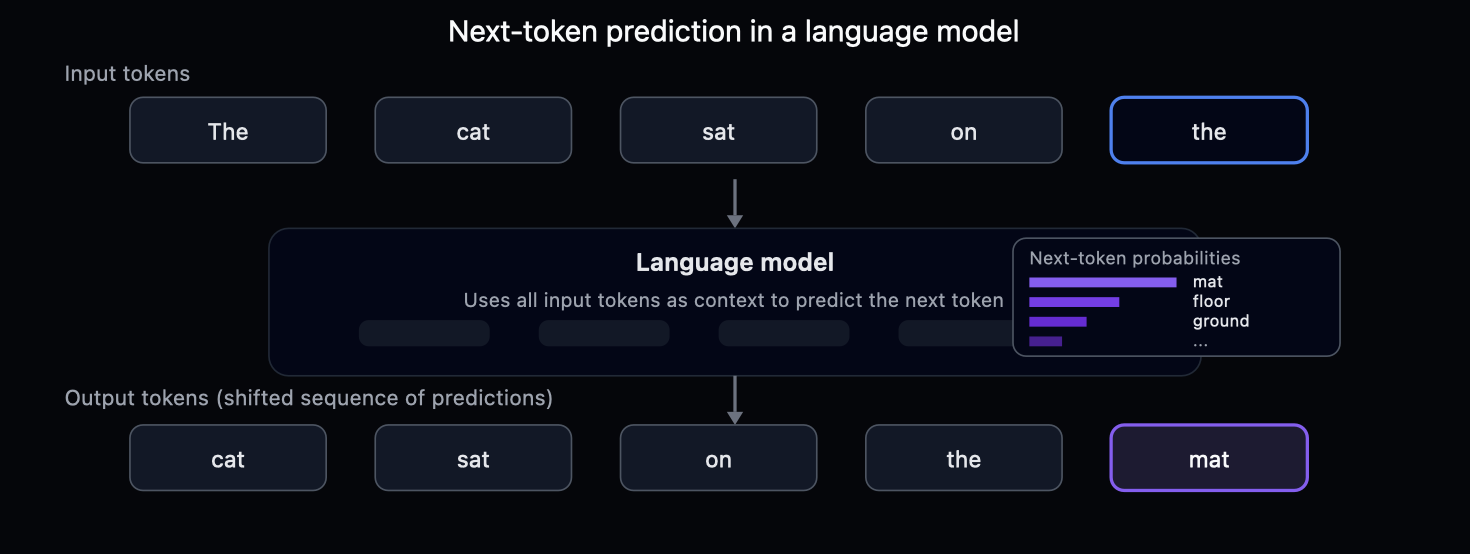

Although the way we interact with chatbot LLMs is through question and answering (where the model predicts an answer given some question), LLMs can operate on raw documents alone. During pre-training, an LLM is trained to predict the next token of a document with nothing other than the previous document tokens as context. This objective can be viewed as a lossy (error-prone) decompression procedure, with the previous tokens acting as a semantic encoding used by the LLM to decode the remainder of the document.

The difference between the predicted next token and the real next token is the quantity of information contained at each point of the document. With the view of LLMs as decompression engines, that is the information required to correct the errors in the decompression process.

You can measure compression efficacy via decompression accuracy

Given the robust decompression error measurement, one can evaluate the quality of a summary by how much it minimizes prediction error with respect to the reference LLM.

Algorithmic overview

At a high level, SQUISH works by measuring the quantity of information the summary contributes to the document, within a constraint of a maximum summary length. Imposing a constraint of a maximum summary length is essential to prevent attributing high scores to trivial solutions. Specifically, a summary which is the same as the original document will achieve a near perfect score as it encodes identical information as the document itself.

As there is no one obvious summary length budget, this constraint is treated as a parameter to the benchmark itself which is run at multiple budget sizes. This is represented as a relative length of the original document (e.g., a summary budget of on a document of characters would mean the maximum length summary would be characters).

# Python-like pseudocode of the SQUISH algorithm

def SQUISH(

ref_model: LLM, document: str, summary: str, budget: float

) -> float:

if len(summary) > len(document) * budget:

return 0.0

document_info = LLM(input=document).information().sum()

# There is a template to prefix the document with the summary,

# with some context for the LLM to explain which each piece of text is which.

# In addition to this template, we need to get a mask so that the

# information calculation only includes the tokens within the document

# (instead of also calculating the information in the summary)

document_with_summary, document_mask = format_document_and_summary(

document, summary

)

document_with_summary_info = LLM(

input=document_with_summary,

mask=document_mask

).information().sum()

# This value represents the quantity of information the summary encoded to assist in predicting the document

information_saved = document_info - document_with_summary_info

normalized_information_saved = information_saved / document_info

return normalized_information_savedJust about when I was done with this project, I decided to redo my literature review, and happened to find that a couple of papers from PrimerAI introduce a similar method to the one I describe here! In particular, they introduce a Shannon Score benchmark which involves a measurement on information saving. However, this method does not apply any constraints to the summary size. That means that the trivial case of the summary being exactly the same as the document produces the maximum possible score on the benchmark. As you'll see below, introducing the summary constraint is essential to creating a reward usable for training a model.

Benchmark results

Using the SQUISH algorithm, I generated summaries from a variety of different LLMs, and evaluated their quality. In the benchmarks, my custom trained 1.7 billion parameter model (small enough to fit on most modern phones) matches the quality of GPT-5 at medium reasoning.

SQUISH@5%

SQUISH@10%

How does training effect the summaries?

Here is a selected example of a summary generated before and after training the custom model optimized using the SQUISH benchmark. As you can see, the model after training manages to generate summaries that are more concise.

Before

After

How to train a model to generate better summaries

Because SQUISH provides a stable metric to evaluate summary quality, it is possible to train a model to optimize for this metric.

Policy gradient

Policy gradient methods are a family of RL (reinforcement learning) methods which optimize the model (the policy) by:

- generating a collection of outputs for some input

- scoring each of the outputs with some reward

- optimizing the model to maximize the reward by increasing the probability of high reward outputs, and minimizing the probability of low reward outputs

Why is SQUISH so useful for RL?

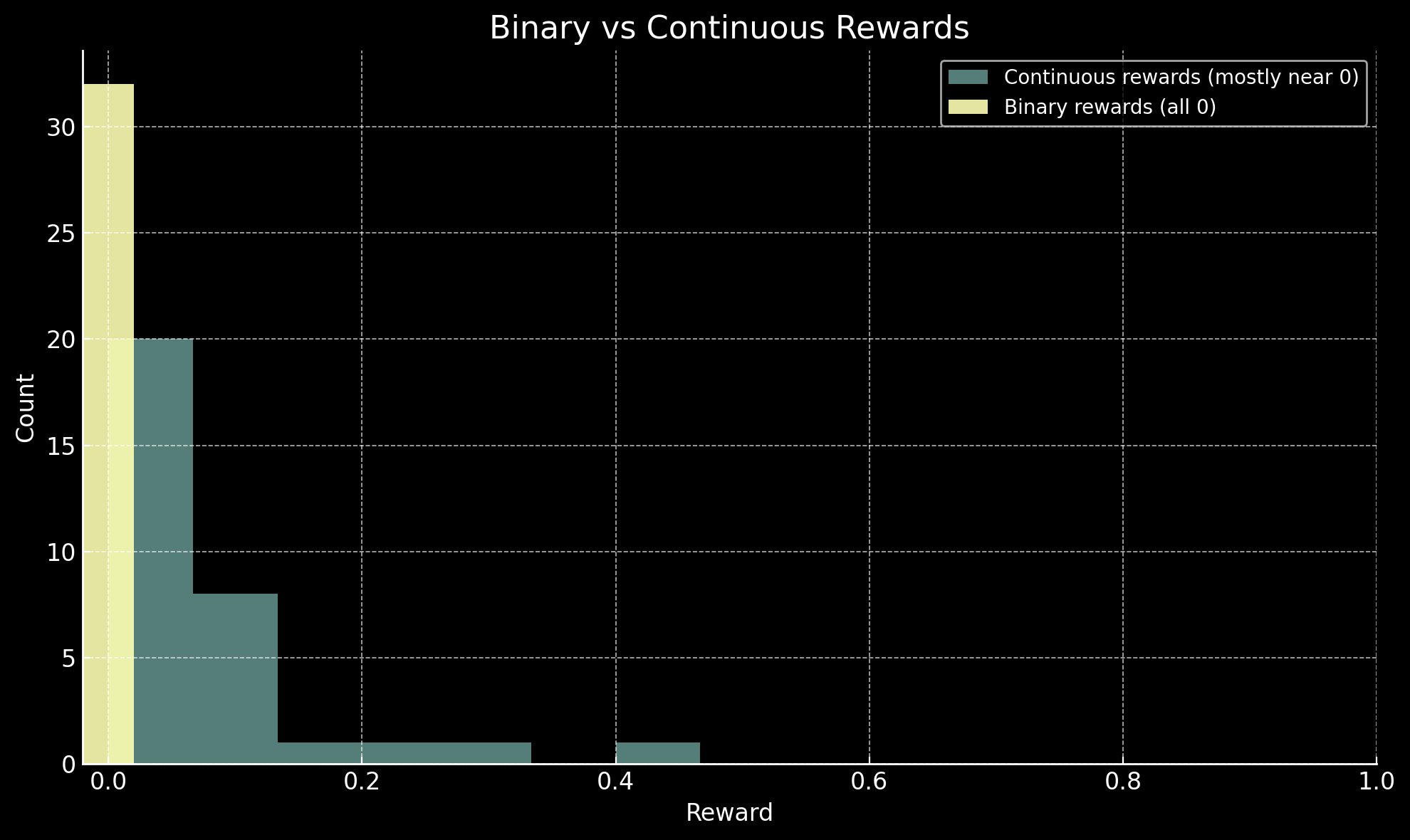

Generally when using RL with verifiable rewards, the rewards are binary in nature. Was the output correct or not? If it's correct, assign a reward of 1, if it's incorrect, assign a reward of 0. In practice this clearly works very well, as DeepSeek showed in their seminal paper introducing GRPO for DeepSeekMath.

However, later research found pitfalls with binary rewards. In particular, the ByteDance team noted in their DAPO paper that many problems in a dataset may be either hard enough that all generations are wrong or easy enough that all generations are right. In these cases, there's no opportunity to learn a better policy as every reward is the same.

For the SQUISH reward, we receive a much higher density signal than common binary rewards, since the reward is any real number between 0 and 1 instead of exclusively 0 and 1. In theory, any pair of non-identical generated summaries provides a learning signal, as the reward will be distinct between each generation. This side-steps the issue of having a collection of generations with no signal.

Additionally, SQUISH does not require a specialized dataset for evaluations. Any document can be used, which allows us to re-use existing document datasets to train and test this benchmark.

The current iteration of SQUISH-bench uses Allen AI's c4/newslike dataset, which is a collection

of English language documents from Common Crawl (a regularly updated open source dataset of the internet)

which are classified as being news-like.

Implementation

Although there are plenty of libraries that exist to handle RL for you (TRL, Unsloth, VERL, prime-rl), I decided to implement (almost) everything with plain PyTorch for 2 separate reasons:

- I knew it would be a valuable learning experience to truly understand how RL (and modern policy gradient methods) work from the ground up. No offloading my understanding to some other piece of software.

- There are parts of the training loop that required minor custom implementations, which is only made more difficult by using the above frameworks. Unsloth actually does support this quite well, but for reason (1) I still hand rolled my code.

How to work around hardware limitations

One of the core constraints that makes building the training loop for SQUISH interesting is that it requires both a policy model and a reference model. This adds quite a bit of VRAM requirements, and a lot of care must be taken to minimize memory usage across every part of the stack (especially if we want to be able to train an effective summarizer model on just 1 RTX 3090).

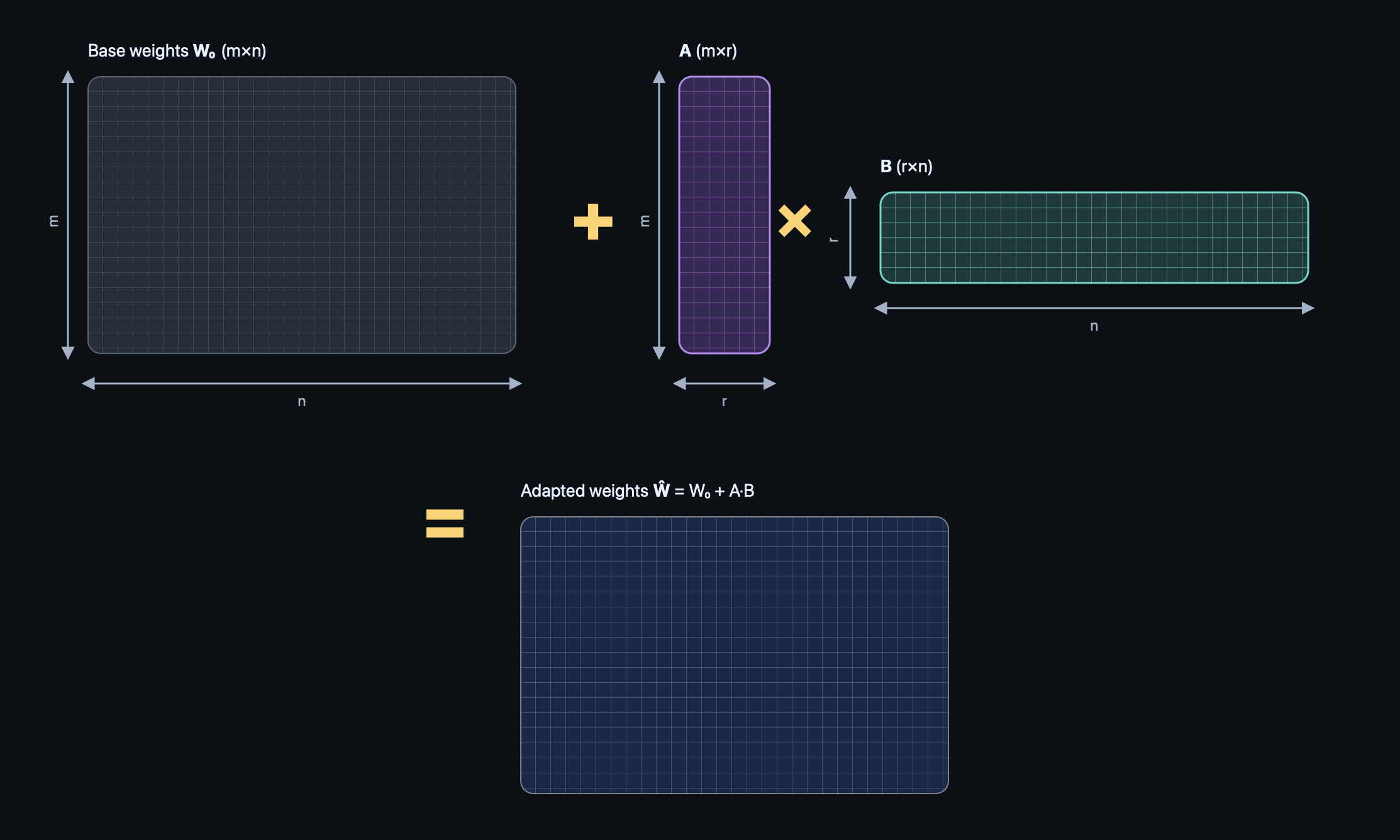

One base model with a policy LoRA

Given the constraint of training a model with SQUISH requiring 2 separate models at once, I decided to use a pre-trained only base model (Qwen 3 1.7B base) as the reference model to evaluate summaries, and train a detachable LoRA over this base model to act as the policy model which generates summaries. The LoRA is active during summary generation and optimization steps, but not during reward calculation. This way, the total memory requirements for both models together is only marginally larger than having a single model in memory (and training becomes faster as well).

Thinking Machines recently made a blog post of their findings on training with LoRA's, which showed that they are nearly identical in performance to full training in the context of reinforcement learning.

The choice to use a base model instead of a chat model for summary generation means early rewards are worse due to poor instruction following, but in practice this didn't prevent the model from achieving very high performance.

Model and loss function compilation

Another critical issue that arises during training is the massive amount of space that intermediate calculations occupy. These come in two forms:

- Intermediate calculations within the core transformer architecture

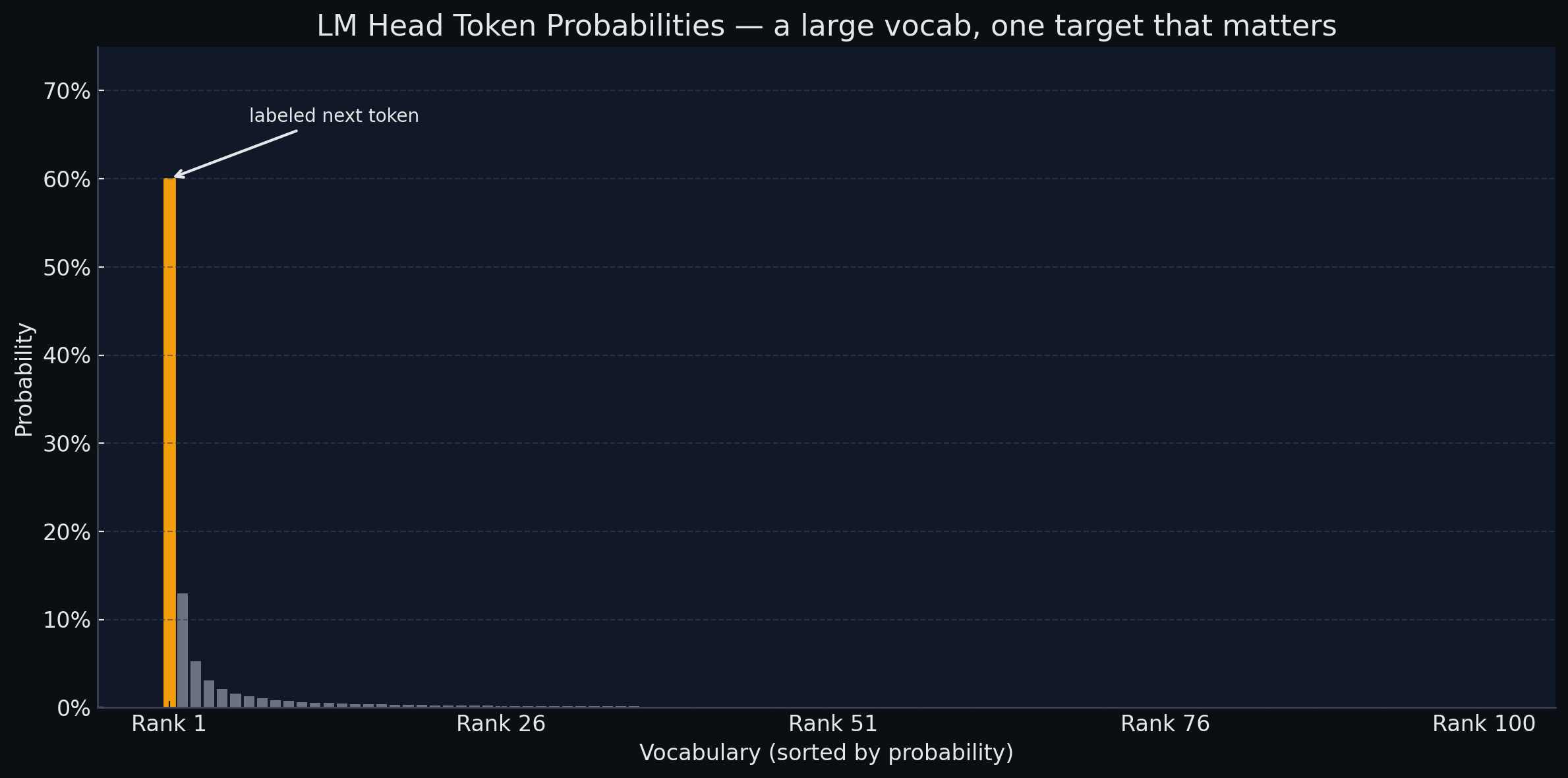

- The final vocab projection probabilities at every token position

- As a rough calculation this would occupy

vocab_size * num_tokens * 4 bytes(for float32 probabilities) - This is approximately

150,000 vocab elements * 4000 tokens * 4 bytes= 2.4GB for one single sequence

- As a rough calculation this would occupy

Both of these issues are solvable by using torch.compile(). The first issue is

handled by compiling the model itself, and the second issue is handled by compiling the loss

function. Torch compilation does operator fusion, which prevents intermediate calculations from

materializing fully into memory. Instead, only the subsection of the intermediate calculation

necessary for the final result is captured at any given point in time.

In the case of the loss function which includes the vocab projection, all but one of the vocab probabilities can be discarded since we only care about the probability of the selected token during both training and summary evaluation.

Gradient checkpointing

Even though we are able to avoid storing intermediate calculations with torch.compile, when you train any model with gradient descent, you must also retain the activations at each

step of the model's execution. This is necessary in order to calculate the gradient of that step's

parameters during back propagation.

Unfortunately activations can be very large.

Fortunately pytorch offers a very simple solution for this called "gradient checkpointing".

Gradient checkpointing should probably be renamed, since it does the opposite of checkpointing. It discards all saved activation in a functional block except for the first one (saving memory), and recalculates activations on the fly during the backwards pass. This is also giving us a VRAM saving boost, but at the cost of more computation which slows down training a bit.

Gradient accumulation

Small batch sizes can hurt training stability and result in mode collapse as described below. However large batch sizes also increase memory requirements. We can work around this using gradient accumulation, which simulates the same dynamics of a larger batch size while having a smaller real batch size.

It works by running a series of separate micro-batches through the model, which add up to the target batch size. Only after all of the micro-batches in a full batch have been run through the model is an optimization step run.

Preventing mode collapse

One problem I ended up spending ~1/3 of my time on in this project was mode collapse. Initially training the summarization model would proceed effectively, but eventually the generation entropy would entirely collapse (meaning all generated summaries for a given document would be the same). When this happens, learning halts, as learning requires a differential between the reward across different generations.

Increasing batch and group size

The most straight forward solution to prevent entropy collapse is increasing the batch and group sizes (the number of inputs and generations per input respectively). With small batch and group sizes, the model can learn at each training step that the optimal policy exists within a very narrow subset of all possible behaviors.

Fortunately increasing both batch and group size becomes extremely easy after implementing gradient accumulation. This was a critical step to make training last long enough to match GPT-5 quality.

Ablations

The most notable ablations in this project were with regard to the summary penalty. Two different approaches were selected to constrain the summary:

- Penalize the quantity of information within the summary from the information saved. Include a tunable parameter to modulate the contribution of the penalty.

- Set the summary length budget to an absolute value, instead of a relative value. For example, 500 characters instead of 10% of the original document.

Summary information penalty

When penalizing the information in the summary, the adjusted reward would always be negative (except for trivially small values of ). I believe this is due to the fact that any information that would help predict the document will also appear in the summary. Ultimately, this led me to realize that this penalty was not measuring something useful.

Absolute summary length penalty

Setting the summary length budget as an absolute value worked much better, but still had its own issues. The intention behind an absolute length budget is that it falls more in line with human preferences generally. If I only have a minute to read something, I want the summary to be within the range of 1000 characters. I don't really care if those 1000 characters are 1%, 5%, or 20% of the original document.

Training with the absolute summary length penalty does actually work quite well, but the benchmark itself becomes biased. Since the final benchmark scores are normalized by the amount of information in the total document, the exact distribution of document sizes within the test set biases the scores. Shorter documents will receive higher scores and longer documents will receive lower scores.

Using token budgets instead of character budgets

I never actually ablated this approach, but I wanted to bring up why I didn't implement it for the benchmark (and why you SHOULD implement it for your own model). Token budgets instead of character budgets are actually a much more relevant metric in cases where you want to provide your summary back to the LLM itself (like in context compaction for coding agents). Additionally, setting the budget on a token instead of character level is less biased for the information measurement, as information itself is measured on the token level.

However, every model is using a different tokenizer, and it's difficult to create a fair constraint that works across different tokenizers when each model will see the same summary and document as different numbers of tokens. If you aren't actively comparing different model families against each other, and don't have character level constraints (like UI space), training with token budgets instead of character budgets is probably better.

Future work

More work to prevent decreasing entropy

Although I was able to keep entropy much higher than initial training runs, entropy still decreases over the course of training. My best intuitive guess as to why this happens is that the model is trained to generate high quality summaries in 1 shot, instead of reasoning before-hand. Quite a lot of RL research is done on reasoning instead of instruct models, and I believe the reasoning trace may be acting as an entropy pool of sorts. Since the reasoning trace itself is not evaluated for rewards, there can be a lot more diversity in reasoning traces that result in similar final outputs. However this entropy pool doesn't exist in instruct style generations, which narrows the diversity of "correct" answers.

Generate summaries with reasoning

In light of the point above, reasoning may afford greater diversity in output generations. Additionally, they may result in generally higher scoring summaries due to the combination not only increased entropy, but also increased planning. As we can see from the benchmarks, the reasoning versions of most models outperform their instruct counterparts. This wasn't attempted in the original implementation due to complexity with format following and memory costs.

Model Ensemble

Currently only Qwen3-1.7B-base is being used as a reference model. However, it would be preferable to include a few different model families (LLaMA, GLM, etc...) to balance the biases inherent to a base model's pretraining data mixes.

More diverse training and test datasets

The current dataset is english and news-like only. Although I believe that is unlikely to have a severe impact on the general trends found in the benchmark, it would obviously add resilience to include a corpus of non-english languages and other topics (such as fiction, academic writing, essay's, etc...).